They are two of the world’s oldest civilizations, two vast mirrors of human memory — India and China. For centuries, they have spoken through philosophy, poetry, and empire. Today, they speak through cinema. Not in the same tongue, not with the same rhythm, but with a shared desire: to be remembered.

Not by numbers, but by myth.

India and China cinema do not compete — they coexist, like two rivers flowing from opposite mountains, sometimes invisible to each other, yet both moving toward the same ocean: global influence.

The Indian Screen

Indian cinema breathes like a crowded festival. It does not fear contradictions — joy interrupted by grief, celebration followed by tragedy. Its films sing because life sings. Families quarrel, lovers part, villages rise and fall, but somewhere a song tries to hold it all together.

It is a cinema born not from discipline, but devotion. Audiences enter not to watch characters, but to meet them — the mother, the rebel, the dreamer, the divine fool. The lines between theater and worship blur. Stars are not performers; they are promises. Even the poorest viewer, sitting in an old single-screen hall, believes that somewhere on the screen, he will find a reflection of his own struggle.

But this devotion has a cost. Indian cinema can be chaotic, overlong, indulgent. It argues with itself. It forgives too easily. Yet in that imperfection lies its courage — it chooses emotion over structure, tears over logic. It may stumble, but it never stands without feeling.

The Chinese Screen

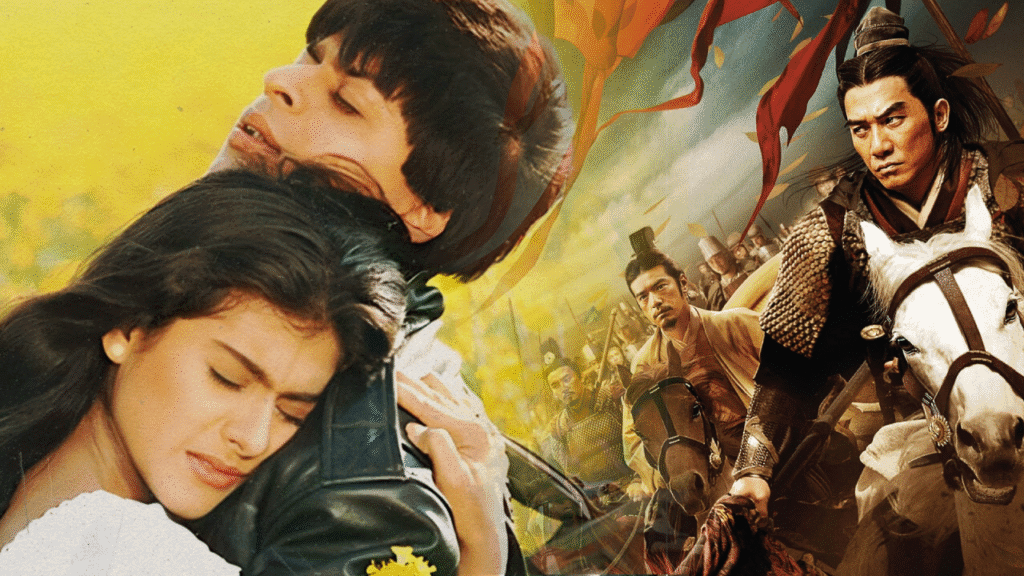

China’s cinema enters like a procession — disciplined, composed, knowing exactly where it must stand. It does not ask for love; it demands attention. Rooted in dynasties, legends, and bloodlines, it carries the memory of emperors and warriors, of silk and steel.

Where Indian films sway, Chinese films strike. Martial epics draw swords not merely to fight, but to honour tradition. A single frame may hold the weight of a thousand-year-old belief. Even in modern productions, there is an echo of ancient scroll paintings — elegant, deliberate, almost ceremonial.

Here, the filmmaker often works under shadow — the shadow of the state, of history, of silence. But from that restraint emerges an unusual strength: precision. If Indian cinema is a poem sung in the streets, Chinese cinema is a monument carved in stone.

Yet this monument, too, has its cracks. In pursuit of grandeur, it sometimes loses softness. It is powerful, but rarely intimate. It conquers the eye but hesitates with the soul.

Two Sources of Power

The greatest difference between the two lies in their source of cinematic energy. India’s cinema is powered by the people. Films survive because audiences believe they belong to them — quoting lines, mimicking stars, dancing at weddings to songs from decades ago. It is democracy on celluloid. China’s cinema is powered by the nation. Its grand narratives carry the voice of a collective, the pride of a civilization determined to define itself against the world. It is not personal storytelling; it is historical memory.

Their Global Struggle

The world sees Indian cinema as emotion; dancing, dreaming, weeping. It sees Chinese cinema as spectacle; warriors, dynasties, revolutions. Both identities are true, yet incomplete.

Indian cinema travels through diaspora, weddings, nostalgia. A grandmother in Canada watches the same melodrama as a teenager in Mumbai. China travels through festivals, film craft, global co-productions, through images that need no translation, a warrior floating through bamboo forests, a general leading armies into mist.

One asks, “Do you feel me?”

The other asks, “Do you see me?”

Beneath every camera, in Mumbai or Beijing, lies the same silent desire to outlive time. To turn national memory into global myth.

When an Indian film ends with a tearful reunion, and a Chinese film concludes with a warrior riding into legend, both are saying the same thing: “Remember us.”

Two Eyes of the Same World

Will the world choose between emotion and precision? Between the song and the sword?

No. The future of cinema is not singular. It has two eyes: One that cries, One that contemplates.

And together, they see more.

In the end, the race between Indian and Chinese cinema is not toward victory, but legacy. One day, long after box office numbers fade and markets shift, a viewer somewhere in a country that belongs to neither will sit in a dark room and watch a film. They will not ask if it came from India or China.

They will simply ask, “Does it move me?”

And if it does, both civilizations will have won.

Read More: