Fifty years after its first release, Sholay returns to theatres on December 12, 2025, not just as a nostalgic re-run, but as a carefully restored “Final Cut,” offering audiences a chance to see the film as originally intended. This milestone invites us to revisit what made Sholay endure across generations, and to re-examine it through the lens of changing times. What follows is a balanced look at its continued power, its contradictions, and why (even in 2025) Sholay still matters.

What Sholay Was — And What It Gave Indian Cinema

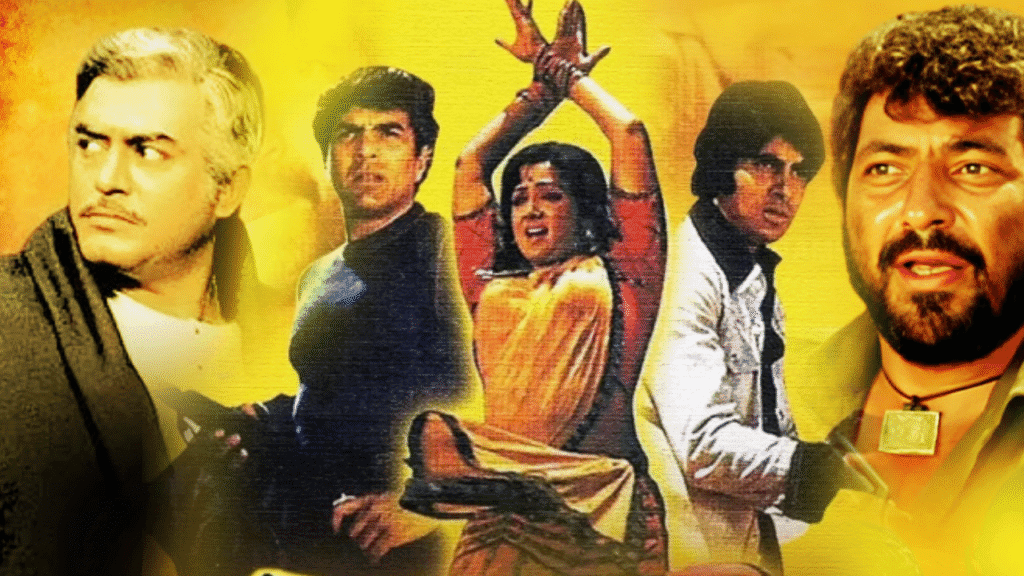

When Sholay premiered in 1975 under the direction of Ramesh Sippy, it did not immediately explode at the box office. The first two weeks were slow. But from the third week onward, word-of-mouth turned it into a phenomenon — and it went on to become the highest-grossing Hindi film of its time, maintaining that status for 19 years.

Sholay fused together genres: action, tragedy, drama, comedy, romance — in a “masala” structure that felt epic, ambitious, and emotionally immersive. Its roots borrowed from Western-style cinematic templates (like the Hollywood Western) but were carefully “Indianised”: the result was familiar yet fresh.

This blend revolutionized Hindi cinema, shifting expectations about scale, tone, narrative arcs, and cinematic texture. For many filmmakers and audiences, Sholay redefined what a “big” Bollywood film could be.

Much of Sholay’s power derives from its characters — from the easy-charm of the outlaw-turned-heroes to the chilling menace of the villain. The duo of protagonists — the fun-loving, loyal Veeru and the quieter, more introspective Jai — symbolised “rogue masculinity,” a moral complexity rarely attempted before in Hindi film.

On the other side stood the ruthless bandit Gabbar Singh — whose brutality was terrifying, yes, but whose mannerisms and dialogue injected fear and fascination.

Songs like Yeh Dosti Hum Nahi Todenge, and the film’s dialogues seeped into popular culture. What began as lines on a script became part of everyday vernacular, quoted, referenced, remembered — binding generations through shared memory.

Sholay held the record for several decades — longest theatrical run in many theatres, “golden jubilees,” “silver jubilees.” It anchored itself not as a fleeting success but as a cultural phenomenon; people didn’t just watch Sholay, they lived it again and again.

Its ambition changed what filmmakers dared to dream, and its success proved that audiences craved stories that were larger-than-life, morally ambiguous, emotional, violent, lyrical — a vast spectrum. In that sense, Sholay didn’t just reflect its time; it shaped decades of Bollywood aspirations.

Why “Sholay – The Final Cut” Matters

The upcoming re-release is not just a re-screening. The film has been restored in 4K, with improved sound (Dolby 5.1), and is being released across 1,500 theatres nationwide. This offers audiences, old and new, a chance to see Sholay on the big screen, with the technical fidelity that modern cinema standards afford.

More importantly for the first time since 1975 the original, un-censored climax will be shown. The ending that was changed due to censorship under India’s Emergency regime (when the final act in which Thakur kills Gabbar was deemed “too violent”) will now be reinstated.

This is not just about nostalgia or indulgence. It is an act of cinematic restoration, a return to the filmmaker’s original vision, offering completeness. For film historians, critics, artists, and audiences alike, it’s an opportunity to re-evaluate the film on its own terms.

For viewers who watched Sholay decades ago, perhaps in the 70s, 80s, 90s, the re-release is a pilgrimage: a chance to re-live memories, revisit emotions, and re-evaluate the film’s impact with the wisdom of age. For younger audiences, it’s history; a bridge to understand not just the film, but the context of Indian cinema, the aesthetics of another era, the art of storytelling before digital or streaming overwhelmed the medium.

The restored cut might also spark debates, on violence, on morality, on representation, all through the lens of a film considered a “classic.” And given how drastically social sensibilities have evolved in 50 years, that conversation could be both uneasy and illuminating.

The Shadows Behind the Legend — Critiques & Contemporary Lens

Scholars have long argued that Sholay glamorizes violence and vigilante justice. The film blurs the boundary between criminality and heroism by presenting two small-time thieves (Jai and Veeru) as saviours — a seductive narrative of “antiheroes turned righteous,” where social justice is enacted outside law.

Moreover, violent sequences, the dacoits assaulting a village, terrorising innocents, brutal confrontations are shown with spectacle, heightening drama but cushioning moral complexity. Some critics argue the film’s catharsis comes at the cost of depth; it gives violence an aesthetic appeal and a moral justification, without sufficiently questioning its social roots or consequences.

From a 2025 vantage point when cinema increasingly acknowledges trauma, responsibility, nuance these aspects can feel troubling.

The female characters in Sholay though memorable in their own right, exist largely in relation to male arcs. Their agency is limited; their roles often revolve around suffering, victimhood, or being objects of desire/romance/comic relief.

Social and community representation too has drawn criticism. Earlier scholars have pointed out stereotypical portrayals of minority or marginalised characters, sometimes caricatured, sometimes treated as buffoonish relief.

Viewed through contemporary social sensibilities, these aspects can appear regressive, and they highlight how much has and perhaps should change in the morality of mainstream storytelling.

Because Sholay is often treated as sacrosanct “the greatest Hindi film ever made”. There’s a tendency to view it without critique; to romanticize its flaws or overlook them. Critics argue that its popularity built on heroic myths, escape from socio-political realities, and individualistic redemption rather than addressing root causes of violence, injustice, poverty or oppression.

As we revisit it now, there is value not just in celebrating Sholay, but in re-examining it, understanding its powers, but also its limitations. Nostalgia should not blur critique.

Filmmakers, Viewers & Memory

Sholay remains a case study in scale, ambition, narrative audacity, and crowd engagement. Its structure, its blending of genres, its character-driven drama, its dialogues — all remain reference points. Yet the re-release challenges creators to ask: can we retain ambition and spectacle while being socially conscious, nuanced, and responsible?

The re-release is a time capsule. It offers a rare chance to relive memories, to feel cinema of another era, but also to reflect on how tastes, values, and sensibilities have changed over five decades. Watching its 4K restoration, audience will see Bollywood before the digital explosion, before streaming, before globalisation, before the fragmentation of film audiences. They will see the power of myth-making, and why stories like these resonated then.

The re-release invites conversation. It asks: what do we choose to celebrate? What do we question? How do we honour classics without turning them into untouchable relics? In 2025, when media, identity, representation and ethics are hotly debated, seeing Sholay again can be instructive for cultural introspection.

Magic & Mirror

Sholay at 50 is more than an anniversary; it’s an invitation. An invitation to re-watch with awe, to re-assess with scrutiny. The restored 4K “Final Cut” ensures that what audiences see is not filtered nostalgia, but the original cinematic vision, grain, flaws, grandeur, violence, emotion, all intact.

The film’s mythic status is understandable: it tapped into collective fears, hopes, loyalties, and delivered a saga that millions carried in memory. But time demands reflection too. As we cheer “Kitne aadmi the?” once more, we might also ask: what did we celebrate then, what do we see now, and what does it mean to be a legend?

For viewers, filmmakers, critics — this re-release offers both a tribute and a mirror. Sholay remains magical. But ideally, after watching it now, we emerge not just enchanted, but awakened.