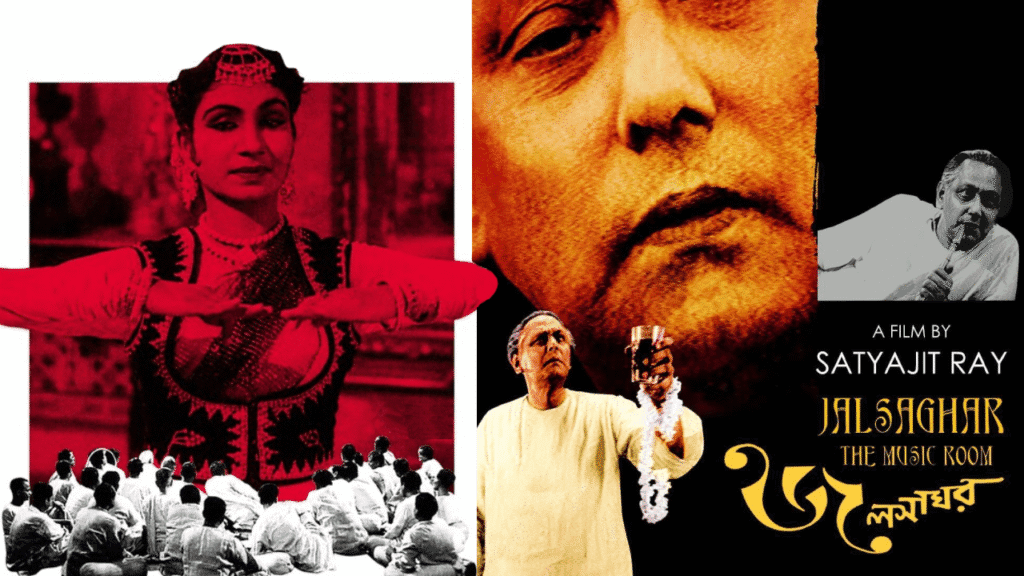

Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958) remains one of the most haunting and visually poetic films ever produced in Indian cinema. Released on 10th October 1958, this cinematic gem has endured for over six decades, yet it continues to shake the very core of human insecurities with astonishing force. While the Apu Trilogy often commands the spotlight in discussions about Ray’s genius, Jalsaghar deserves equal, if not greater, reverence for its profound psychological depth and visual mastery.

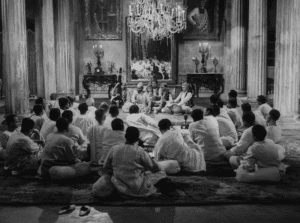

At its heart, Jalsaghar is the portrait of Biswambhar Roy (played by the magnificent Chhabi Biswas), a proud zamindar trapped in the ruins of his own grandeur. His music room, once a symbol of opulence and cultural refinement, has become a mausoleum of memories, where chandeliers flicker like dying stars and dust gathers on relics of faded glory. Through this single decaying space, Ray captures not only the twilight of an individual but the decline of an entire class, the feudal aristocracy of Bengal fading under the dawn of modern India.

Ray’s genius lies in how he transforms this decline into visual poetry. Every frame feels like a painting, composed with quiet precision and emotional gravity. Despite being set within a vast mansion, the film exudes an uncanny claustrophobia. The wide, echoing halls and ornate ceilings, instead of breathing freedom, imprison Roy within his own illusions. Ray makes grandeur feel suffocating — a metaphor for a man trapped by pride and nostalgia in a world that has already moved on.

The most unsettling and unforgettable image arrives during one of the musical soirées — a mesmerizing blend of sound and silence, wealth and decay. Roy notices an insect struggling inside his wine goblet, its fragile body convulsing as it drowns in crimson liquid. It is one of the most chillingly symbolic moments in world cinema. On one level, it foreshadows the tragedy that awaits him — the storm, the river, the death of his wife and son. But more profoundly, it mirrors Roy’s own internal disintegration. Like the insect, he too is suffocating within the intoxicating glass of his own vanity, unable to adapt, unable to escape. The beauty that once defined his identity now becomes the very instrument of his doom.

Throughout Jalsaghar, Ray uses silence as powerfully as he uses music. The rhythm of the film shifts between the lushness of the performances and the stillness of Roy’s solitude. The flicker of the chandelier, the echo of footsteps across marble floors, and the long pauses between musical notes all evoke a slow death — not only of a man, but of an era. Even the camera seems to mourn as it glides through the decaying corridors of the mansion, framing Roy like a ghost haunting his own legacy.

More than sixty-five years after its release, Jalsaghar still resonates with unrelenting intensity. Its themes — insecurity, ego, resistance to change — are as universal today as they were in post-colonial India. In its stillness lies turbulence; in its beauty, decay; in its silence, a scream.

Jalsaghar is not merely a story of one man’s downfall — it is a requiem for a civilization’s passing, rendered through the eye of a filmmaker who saw humanity’s fragility with extraordinary empathy. It stands, unquestionably, among the greatest films ever made in India — a masterpiece that, like its doomed zamindar, continues to shimmer long after the music has faded.

Read More:

- The Evolution of Indian Cinema: From Satyajit Ray to Anurag Kashyap

- When Fiction Predicts Reality: Movies That Became True