There is something quietly transformative about the stories we share with our children. These tales, wrapped in wonder and mischief, dreams and dilemmas, do more than entertain—they carry the emotional and moral compass of a society. A children’s film is rarely just a film. It’s a whisper from one generation to the next, a reflection of what we cherish, what we fear, and what we hope for.

Unlike many genres that are shaped by trends or market demands, children’s cinema is shaped by something deeper: care. Care for what children grow up believing, imagining, and becoming. It is in this space of gentleness and intention that children’s films quietly document the state of a nation.

They may not be political in the traditional sense, but they are deeply social. A children’s film often reveals more about the soul of a country than its political speeches or policies. It shows us how we talk to our youngest citizens, how we prepare them for the world, and what kind of world we want them to inherit.

Children’s Stories, National Realities

Children’s cinema, across the world, often reflects the mood of its people. In countries where children grow up surrounded by conflict or hardship, their stories tend to carry a tone of realism. These films do not shy away from showing life as it is, but instead, they do so through the soft gaze of childhood—never losing hope, never letting go of dreams. In more affluent or politically stable countries, the emphasis shifts toward fantasy and self-discovery, exploring internal journeys through adventure and imagination.

Neither approach is better or worse; each simply reveals what society considers most important for its children to understand. Is it more important to preserve innocence, or to prepare children for the complexities of life? Are we offering escape, or equipping them with empathy?

In either case, a nation’s children’s films reflect its emotional landscape. They show us how we’re raising the next generation—not just in homes and schools, but in our collective cultural consciousness.

The Indian Lens

In India, children’s cinema is often stuck between two extremes—either too didactic or too fantastical. The mainstream industry tends to see children’s films as commercially unviable, often relegating them to government-funded projects, festivals, or educational spaces. And yet, India is home to some of the richest, most layered childhoods in the world—filled with contradictions, culture, chaos, and colour.

Indian children navigate a complex web of tradition and modernity. They’re exposed to stories from grandparents, mobile screens, textbooks, and mythologies all at once. Their lives brim with narrative potential. Yet, how often do we see those authentic childhoods reflected on screen? Too rarely.

There is a need for stories about small homes, big dreams, quiet friendships, and fleeting moments that shape who we become. When children are treated as intelligent viewers, capable of feeling deeply and thinking critically, they respond with immense warmth and understanding. And so do adults.

What is most heartening is how people—regardless of language or geography—connect with these stories. Childhood, in its essence, is universal. Its joys and vulnerabilities transcend borders.

Reflections from the World

Looking beyond India, the relationship between national identity and children’s cinema becomes even clearer.

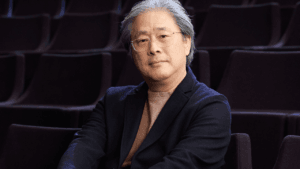

In Iran, for instance, children’s films have long held a special place in cinematic storytelling. A film like Children of Heaven, directed by Majid Majidi, is a beautiful example. On the surface, it’s a simple story about a brother and sister who share a single pair of shoes. But beneath that simplicity lies a deep meditation on dignity, compassion, and survival. The film never overstates its emotion. It trusts the audience—child or adult—to feel the unspoken. And in doing so, it presents a portrait of Iranian society that is both tender and truthful.

Japan, too, has offered the world some of the most poignant children’s films. Grave of the Fireflies, though animated, is a hauntingly real depiction of war through the eyes of two siblings. The film doesn’t protect its audience from pain. Instead, it shows that even in the darkest times, the love between a brother and sister can become a source of light. Through its storytelling, the film speaks to Japan’s collective memory of World War II and its commitment to peace and remembrance.

Closer to home, Taare Zameen Par marked a turning point in Indian mainstream cinema’s approach to childhood. It portrayed a dyslexic boy not as a problem to be fixed, but as a child with a unique way of seeing the world. The film encouraged a shift in how we view education and parenting, and it did so with warmth, imagination, and empathy.

And then there are smaller, quieter films that may not have the reach of blockbuster cinema, but still carry within them the heartbeat of a community. They tell stories that might otherwise be forgotten. Stories of resilience, of small acts of rebellion, of silent dreams.

Why It Matters

When we reflect on the state of children’s cinema, we’re also reflecting on how we view childhood itself. Are children seen as passive recipients of values, or as active participants in shaping the world? Are we offering them escapism, or encouraging curiosity? Do we talk down to them, or trust their intelligence?

The answers to these questions are not just cinematic—they’re cultural. And they reveal the spirit of a society.

Children’s films remind us that even the smallest moments—a shared lunchbox, a fight between friends, a chase through narrow gullies—carry meaning. They show us the emotional terrain of young minds, and in doing so, they gently guide us back to our own childhoods. They heal, they question, they laugh, and they listen.

Most importantly, they plant seeds. Seeds of empathy, wonder, and courage.

A Gentle Revolution

To invest in children’s cinema is to believe in a better tomorrow. It’s an act of faith. These films may not always make headlines, but they make a lasting impression on hearts. And when done well, they carry the power to shape how children see the world—and how they see themselves within it.

As filmmakers, educators, parents, and storytellers, we carry the responsibility to make this space richer, kinder, and more imaginative. Not by creating perfect stories, but by creating honest ones.

Because in the end, the stories we tell our children are the stories we are telling ourselves—about who we are, and who we still hope to become.