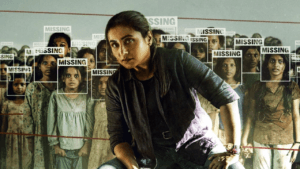

No Good Men opened the latest edition of the Berlin International Film Festival with a film that is lighter in tone than its political backdrop might suggest. Written and directed by Shahrbanoo Sadat, the Afghan-set romantic comedy unfolds in 2021, shortly before the Taliban’s return to power — a setting that quietly deepens what might otherwise appear to be a conventional love story.

At the center is Naru, the only camerawoman at Kabul’s main TV station, who is fighting to retain custody of her three-year-old son after leaving her serially unfaithful husband. Disillusioned and convinced that no good men exist in her country, she navigates a city on the brink of upheaval. When Qodrat, the station’s star journalist, offers her a professional opportunity, the two begin reporting together across Kabul during what are effectively the last days of relative freedom. As they criss-cross the city covering unfolding events, romantic tension grows — and Naru begins to question her certainty that goodness has disappeared from the men around her.

Critics largely agree that this political framing lends the film its most compelling undercurrent. At Screen Daily, the film was described as “a breezy, crowd-pleasing romantic comedy that opens the Berlinale on a charming note,” though the publication noted that “its lightness is both its strength and its limitation.” That tension is key: the backdrop suggests urgency and historical gravity, yet the storytelling favors intimacy and accessibility.

Variety called the film “an amiable and accessible Berlin opener that plays it safe within familiar rom-com beats,” while acknowledging that it “offers warmth and cultural specificity, even if it rarely surprises.” The cultural specificity here is particularly tied to the newsroom setting — a workplace that doubles as a symbol of fragile civic freedom.

At The Hollywood Reporter, the film was labeled “a pleasant but predictable crowd-starter,” with the caveat that its “breeziness occasionally borders on the conventional.” The publication pointed to the screenplay’s adherence to traditional romantic arcs, suggesting that the dramatic potential of the political moment is only partially explored.

The British press echoed this tempered admiration. The Guardian described the film as “light-footed and gently amusing, though dramatically modest.” That modesty appears to stem from Sadat’s decision not to turn the looming political shift into overt melodrama. Instead, the collapse of an era hums in the background, shaping mood more than plot.

Meanwhile, IndieWire framed the film as “a likable festival curtain-raiser that favors charm over complexity.” Yet within that charm lies a more layered narrative: a woman negotiating autonomy, motherhood and professional ambition in a society whose freedoms are visibly narrowing.

Technically, critics have praised the film’s craft. Cinematography by Virginie Surdej captures Kabul with warmth and immediacy, balancing domestic interiors with newsroom urgency. Production design by Pegah Ghalambor and costumes by Pola Kardum contribute to a sense of lived-in authenticity, reinforcing the realism of Naru’s world rather than romanticizing it. Editing by Alexandra Strauss maintains a light, fluid pace, ensuring the film never tips into heaviness despite its setting.

The score, composed by Harpreet Bansal, Therese Aune and Kristian Eidnes, subtly underscores the emotional beats without overwhelming them. Sound design by Anne Gry Friis Kristensen and Sigrid DPA Jensen further enhances the sense of immersion, grounding scenes in everyday textures rather than spectacle.

Where critics diverge most is in assessing how fully the film leverages its historical moment. Some reviewers suggest that the romance’s conventional structure — misunderstandings, gradual trust, emotional hesitations — occasionally softens the impact of the surrounding political tension. Others argue that this contrast is precisely the point: life, love and personal transformation persist even as systems collapse.

What remains consistent across coverage is appreciation for Sadat’s perspective. As both writer and director, she shapes the narrative around a woman’s agency in a society in flux. Naru’s skepticism toward men is not treated as a punchline but as a protective response shaped by experience. Her gradual openness to Qodrat unfolds against a ticking clock, adding poignancy to what might otherwise be standard romantic development.

As a Berlinale opener, No Good Men appears to have succeeded in setting an inclusive tone. It may not be the festival’s boldest or most formally daring entry, but it invites audiences into a specific cultural moment through a familiar genre lens. That balance — between accessibility and specificity — defines the film’s reception.

In the final analysis, critics see No Good Men as safe but sincere. It does not radically reinvent the romantic comedy, nor does it fully interrogate the seismic political shift framing its story. But it offers warmth, cultural texture and a perspective rarely seen in mainstream rom-coms. Against the backdrop of Afghanistan’s final days of freedom, the question posed by its title becomes quietly resonant: in a collapsing world, what does goodness look like — and how do you recognize it before it disappears?

Read More Review Roundups on POF