In a world where lines on a map can turn neighbours into enemies and headlines often paint nations in black and white, cinema quietly slips through the cracks—carrying stories, emotions, and empathy across the very borders built to divide us. Unlike political speeches or military standoffs, a film doesn’t ask for your allegiance. It only asks you to feel. And sometimes, that’s enough to shake the foundations of long-held hostility.

Cinema, at its core, is about human connection. It doesn’t matter what language is spoken on-screen—if a mother’s eyes well up as her child walks away, we all understand. Films give us the rare ability to step into someone else’s shoes, even if they’re from across the border, even if our countries are in conflict, even if everything else tells us we shouldn’t relate. But we dobecause films unite divided nations.

Take Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015) for instance. On the surface, it’s a Bollywood entertainer starring Salman Khan. But at its heart, it’s about an Indian man’s journey to reunite a lost mute Pakistani girl with her family. The film does what years of diplomacy failed to do—it made Indian audiences fall in love with a Pakistani child and made Pakistani viewers weep for a kind-hearted Indian hero. Suddenly, the enemy wasn’t faceless anymore. It was human. Vulnerable. Just like us.

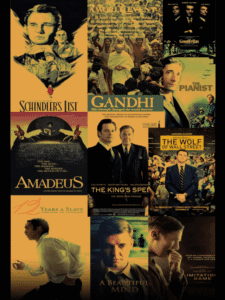

And this isn’t a one-off case. Films have often stepped in where politics has faltered. Think of The Kite Runner (2007), based on Khaled Hosseini’s novel, which gently led Western audiences into the emotional terrain of a war-torn Afghanistan—showing not just bombs and Taliban, but friendship, betrayal, regret, and redemption. It painted a picture of a country often reduced to headlines and drone footage. Cinema did what news couldn’t—it made us care.

Closer home, Indian and Pakistani cinema share a strange, almost poetic relationship. Despite bans, censorship, and frosty relations, people across the border still manage to watch each other’s films. Pirated Drives, YouTube uploads, VPNs—cinema finds a way. Pakistani dramas and films like Bol (2011) or Khuda Kay Liye (2007) have found huge audiences in India. Meanwhile, Bollywood stars like Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol are household names in Pakistan. There’s something deeply ironic about how, even when governments shut borders, the people quietly keep watching each other’s stories in their living rooms.

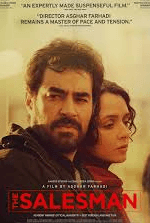

And it’s not just South Asia. Look at Iran and the West. Decades of strained relations haven’t stopped Iranian cinema from receiving standing ovations at international festivals. Directors like Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, The Salesman) or Jafar Panahi (Taxi Tehran) tell deeply local stories that feel universal. In fact, the more specific these films get—grappling with moral dilemmas, family structures, repression—the more they strike a chord globally. Why? Because honesty cuts through nationalism. We may be from different worlds, but the questions we ask—about freedom, love, justice—are eerily similar.

And it’s not just South Asia. Look at Iran and the West. Decades of strained relations haven’t stopped Iranian cinema from receiving standing ovations at international festivals. Directors like Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, The Salesman) or Jafar Panahi (Taxi Tehran) tell deeply local stories that feel universal. In fact, the more specific these films get—grappling with moral dilemmas, family structures, repression—the more they strike a chord globally. Why? Because honesty cuts through nationalism. We may be from different worlds, but the questions we ask—about freedom, love, justice—are eerily similar.

Sometimes, it’s the collaborative efforts that speak the loudest. Take Persepolis (2007), a French-Iranian animated film based on Marjane Satrapi’s life. It told the coming-of-age story of a young girl during the Iranian revolution, combining humour, sadness, and rebellion in a way that resonated across cultures. The film faced bans and outrage in parts of the Middle East, but it found love and understanding everywhere else.

The magic of cinema also finds its strongest allies in film festivals. These events don’t care about passports. A Turkish director, a Syrian refugee, a Palestinian actor, and an Israeli cinematographer might all find themselves in the same screening room. The Cannes, Berlinale, Busan, and even MAMI festivals have time and again showcased films from politically conflicting regions—giving artists a stage where borders don’t matter, and stories are free to fly.

But of course, it’s not always smooth. Cinema that tries to bridge divides often pays the price. Films get banned, screenings disrupted, directors questioned. When Manto (2018), a film about the legendary writer who lived through India’s partition, was released, it reignited debates about freedom of expression and nationalism. But even amid controversy, the film started conversations—about division, about shared trauma, about how art can be dangerous simply by being honest.

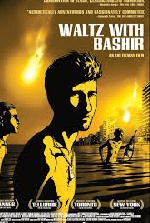

Interestingly, the audiences are often far more open than the authorities. Social media platforms are filled with comments like “I’m from Pakistan and I loved this Indian movie” or “As an Israeli, this Palestinian film broke my heart.” When films like Waltz with Bashir (2008) or Omar (2013) get global attention, they do more than entertain—they challenge narratives, provoke questions, and blur the lines between “us” and “them.”

Interestingly, the audiences are often far more open than the authorities. Social media platforms are filled with comments like “I’m from Pakistan and I loved this Indian movie” or “As an Israeli, this Palestinian film broke my heart.” When films like Waltz with Bashir (2008) or Omar (2013) get global attention, they do more than entertain—they challenge narratives, provoke questions, and blur the lines between “us” and “them.”

There’s also something beautiful in the way films handle nuance. Where politicians speak in absolutes—enemy, threat, terrorist—cinema zooms in. It shows the child behind the soldier’s uniform, the wife waiting at home, the rebel who just wanted to study. These aren’t just character arcs. They’re acts of rebellion against oversimplification. They remind us that people are not policies. That empathy doesn’t need a visa.

And maybe that’s why governments sometimes fear cinema. Because it works. Because one good film can undo years of propaganda. One relatable character can make you question an entire ideology. And once you’ve felt that empathy, it’s hard to un-feel it.

Cinema may not stop wars. It may not change policies overnight. But it plants seeds—of understanding, of curiosity, of peace. And sometimes, those seeds bloom in the most unexpected places.

At Planet of Films, we believe that stories travel faster than missiles, and what binds us is deeper than what divides us. In an age where building walls is easier than building bridges, cinema chooses the harder, nobler path. It reminds us that no matter how far apart we are on the map, in the dim light of a theatre, we’re all sitting together—laughing, crying, hoping—for the same things.

Read More: