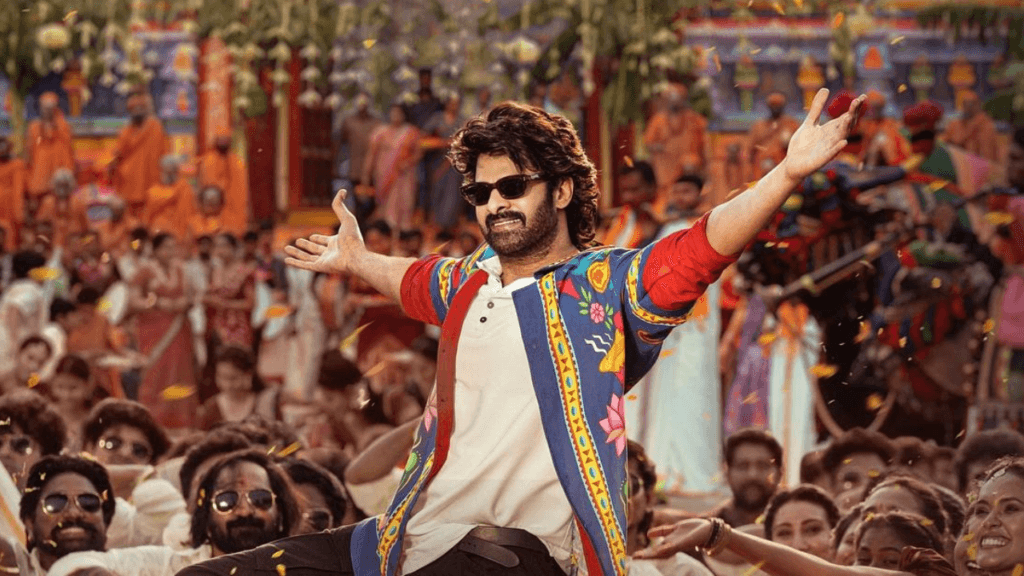

Prabhas’s latest release, The Raja Saab, has crossed the ₹100 crore India Net mark within its opening weekend. For most stars, this would be a moment of unqualified celebration. For a superstar of Prabhas’s stature, however, the milestone lands with an uncomfortable pause. The numbers are big, but the story they tell is far more complicated.

Despite a thunderous opening day, The Raja Saab showed a consistent downward trajectory over its first three days, with one detail standing out sharply: there was no Sunday jump. In Indian box-office analysis, this is the oldest and most unforgiving red flag. When Sunday fails to outperform Friday, even after a massive opening, it signals that the film has struggled to travel beyond its core fan base. At that point, the verdict begins to form quietly, regardless of how impressive the headline figures look.

This is where the conversation must move beyond raw totals and into context.

The turning point in Prabhas’s career, and arguably in the economics of modern Indian stardom, arrived with Baahubali: The Conclusion. That film didn’t just break records; it reshaped audience expectations and industry behaviour. Prabhas became a pan-India phenomenon overnight, and with that elevation came a dangerous assumption — that scale itself could replace scrutiny, and that every subsequent release could be positioned as an “event film” by default.

In the years following Baahubali, budgets expanded rapidly, release strategies grew more aggressive, and marketing often outpaced material. Stardom began to do the heavy lifting before the audience had a chance to respond. This shift created what has now become a familiar pattern: massive openings powered by fandom and anticipation, followed by steep drops once word-of-mouth took over.

Front-loaded box office runs are not inherently disastrous. Many films rely on strong starts. The problem arises when front-loading becomes the entire strategy, especially for films mounted at ₹300–400 crore. At that scale, sustainability matters far more than spectacle. A film is no longer judged by how loudly it opens, but by how long it holds.

The rot didn’t set in overnight. With Saaho, the opening was enormous, but confusion around storytelling quickly drained momentum. Radhe Shyam followed a similar curve, where curiosity drove the initial footfalls and indifference defined the days that followed. Then came Adipurush, a project mounted on unprecedented scale, undone by backlash over execution and creative choices. Each film reinforced the same truth: opening day numbers can conceal structural weaknesses, but they cannot erase them.

To frame this as a decline in Prabhas’s stardom would be misleading. In fact, the clearest proof lies in the films that worked. Kalki 2898 AD didn’t just open big; it sustained because audiences connected with its world-building and long-term vision. Similarly, Salaar justified its scale through genre clarity and repeat value. These films demonstrate that when vision, genre, and scale align, Prabhas’s box-office pull doesn’t just create openings — it creates legs.

Which brings the focus back to The Raja Saab, and why its numbers, while impressive on the surface, raise deeper concerns. The film collected ₹108 crore India Net in its first three days, translating to a gross of ₹129.20 crore domestically and ₹161 crore worldwide. A closer look, however, reveals how heavily the run leaned on Day 1. The Telugu version alone contributed ₹91 crore to the India Net total, with ₹47 crore arriving on the first day after ₹9.15 crore in premieres. Collections then dropped sharply to ₹20.65 crore on Day 2 and slid further to ₹14.2 crore on Sunday. More than half of the film’s Telugu earnings came from a single day, and the absence of any Sunday growth in the home market is a clear signal that the film failed to attract the wider, casual audience needed for momentum.

The Hindi market followed a similar pattern. Starting at ₹6 crore on Friday, collections dipped to ₹5.1 crore on Saturday and fell again to ₹4.65 crore on Sunday, closing the weekend at ₹15.75 crore. Other language markets barely registered, together contributing less than two percent of the domestic total. This is where the “pan-India” label begins to feel less like a geographic reality and more like a marketing ambition. When a film’s footprint remains overwhelmingly concentrated in one region, the justification for pan-India scale becomes fragile.

Globally, overseas collections of ₹31.80 crore helped bolster the opening weekend, but even here the numbers trailed behind Prabhas’s recent blockbusters. Statistically strong does not always mean strategically sound, especially when momentum is missing.

The genre choice compounds the issue. Horror-comedy is an intimate, communal experience that thrives on surprise, writing, and word-of-mouth. It grows when audiences recommend it, not when it is inflated into spectacle. The Raja Saab fell into the trap of genre inflation — stretching a niche concept into a ₹300-crore-plus “event film.” In doing so, the film traded the genre’s inherent charm for a scale that the screenplay could not convincingly support. Unlike action spectacles, which naturally invite repeat viewing, horror-comedy lives or dies by organic audience response. When that response falters, scale becomes a liability rather than an advantage.

This is where the uncomfortable budget conversation enters. A ₹100 crore India Net weekend on a film reportedly costing ₹300–400 crore does not signal safety. It doesn’t even cover marketing and distribution costs. For a film of this size to be considered successful, it typically needs to earn two to two-and-a-half times its budget in gross terms. Without strong weekday holds and long-term stability, the recovery math turns unforgiving very quickly. Early trends suggest that The Raja Saab now faces an uphill climb, one where time works against it rather than in its favour.

None of this points to a collapse of Prabhas’s stardom. On the contrary, few actors today can still command such massive openings across languages. What it does point to is a systemic issue — a machine that increasingly mistakes scale for substance and branding for audience connection. When every film is sold as an event, the very idea of an event loses meaning.

Theatrical audiences haven’t disappeared. They’ve simply become selective. Recent sleeper successes have shown that films can grow slowly and sustainably when they earn trust, even without explosive openings. The seats are still there. What’s missing, more often than not, is a compelling reason to fill them again after Friday.