These days, it’s rare to see an Indian film that begins its journey from the pages of a book. Unlike earlier times, where novels and short stories were a natural source of inspiration for filmmakers, today’s cinema seems to have drifted away from literature. The art of adapting novels into films—once a proud tradition of Indian storytelling—has almost vanished from the mainstream.

A Time When Books Shaped Indian Cinema

During the golden age of Indian cinema, literature played a major role in shaping the films we still admire today. Satyajit Ray adapted several works by Tagore, including Charulata, a beautiful film about loneliness and longing within a marriage. Filmmakers like Bimal Roy adapted Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novels into timeless classics such as Devdas and Parineeta, while Gulzar brought to screen stories full of quiet emotion and deep poetry, like Aandhi and Koshish.

In Hindi cinema, Guide (based on R.K. Narayan’s novel) was a landmark film that explored love, identity, and spirituality. Even mainstream filmmakers didn’t shy away from adapting complex, layered books. They treated the source material with great respect, often keeping the soul of the story intact even while changing its form.

Regional cinema also gave us incredible literary adaptations. In Bengali, Malayalam, Marathi, and Tamil films, there has long been a tradition of drawing from novels, short stories, and plays. These films weren’t just entertainment—they were bridges between literature and the common viewer.

Why These Adaptations Worked So Well

There are many reasons why literary adaptations worked so beautifully in earlier Indian films.

First, the filmmakers themselves were often readers. They loved literature, and that love showed in their work. Directors like Ray and Benegal weren’t just technicians or storytellers—they were thinkers, often deeply connected to books and culture.

Second, the pace of life—and cinema—was slower back then. Makers had more patience for thoughtful, character-driven stories. A scene didn’t need fast edits or loud background music to hold attention. Emotional depth mattered more than dramatic twists.

Third, the film industry allowed more creative freedom. Even in commercial cinema, there was room for different kinds of stories. A good book could be turned into a good film without being reduced to a “product.”

Finally, the line between literature and film was not as wide as it is today. Writers often worked with filmmakers. There was mutual respect. Literature wasn’t seen as something separate or highbrow—it was a natural part of storytelling.

What Changed?

In the last 20 years, the film industry has changed a lot—and so has the audience.

Today, most mainstream films are built around strong plots, catchy songs, and visual spectacle. In this world, slow, thoughtful literary stories are often seen as too risky. Producers are more interested in ideas that can “sell” easily—true crime, famous lives, quick thrillers, or social messages that are easy to digest.

Another reason is the growing gap between the literary world and the film world. Many filmmakers today don’t come from a background of reading. Books are no longer a part of their creative journey. The result? Stories with less depth, less texture, and fewer surprises.

Also, many Indian authors write in regional languages, and their works remain unknown outside their communities. Language becomes a barrier. Filmmakers miss out on these rich sources of storytelling because translation is rare and reading habits are fading.

A Global Contrast

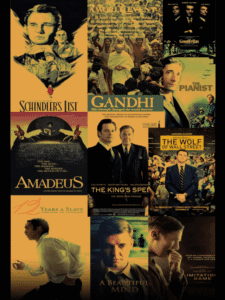

While Indian cinema has largely moved away from literary adaptations, Hollywood continues to embrace them in a big way. Films based on novels, biographies, and even plays are still a significant part of the American film industry. Almost every Oscar season, you’ll find major contenders that began as books—Dune, Little Women, The Power of the Dog, Killers of the Flower Moon, and Oppenheimer, to name just a few. Streaming platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple TV+ regularly invest in adaptations of bestselling novels and critically acclaimed works.

Hollywood understands that a well-written book often offers complex characters, strong themes, and rich worlds—exactly what makes for compelling cinema. There’s also a strong tradition of collaboration between writers and filmmakers, and an entire ecosystem that values the literary source as a marketing advantage. In contrast, Indian cinema has yet to create a similar culture around book-to-screen storytelling.

There Are Still Some Bright Spots

Not all is lost. Every now and then, a film comes along that reminds us of the power of literature.

Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool and Omkara, adapted from Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Othello, gave Indian audiences a fresh way to experience classic plays. The Blue Umbrella, based on Ruskin Bond’s novella, captured the innocence of childhood with grace. Parineeta (2005) was a successful attempt to bring a classic Bengali novel into a modern cinematic space without losing its soul.

In regional cinema, especially in Malayalam and Marathi, the tradition of adapting literary works continues quietly. These industries still have space for smaller, character-driven films. The connection between literature and film is not completely broken—it’s just hidden under the noise.

What We’re Losing Without Literary Adaptations

When cinema stops adapting books, it loses something important.

We lose the richness of inner life—what a character thinks, feels, and hides. Literature gives us access to the mind in a way few other art forms can. Good film adaptations manage to translate that into visual language, often with silence, mood, and subtlety.

We lose stories that don’t follow formula. Many literary stories are unusual—they might be slow, tragic, or even unresolved. But they stay with us longer. They challenge us to think, feel, and look deeper.

We also lose our cultural memory. Many great Indian writers—Qurratulain Hyder, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Ismat Chughtai—wrote about times, places, and emotions that today’s viewers have never known. Films can keep those memories alive, but only if someone chooses to tell those stories again.

Can This Art Be Revived?

The good news is: yes, it can. But it needs effort, vision, and love.

Filmmakers need to read again. They need to fall in love with language and emotion, not just visuals and editing tricks. Producers need to trust that audiences still care about depth. And film schools need to teach students not just how to shoot a scene, but how to feel it.

Streaming platforms have the power to bring back literary adaptations, especially as web series. These platforms don’t need to chase box office numbers, and they can reach niche audiences. But for that to happen, writers and filmmakers must start talking again.

A Quiet Hope

Literature and cinema are both about human truth. When one feeds the other, something beautiful happens. A book becomes a living, breathing world. A film gains layers that stay with you long after the lights go out.

We may not see adaptations like Charulata or Guide every day, but the door isn’t closed. Somewhere, a writer is creating a world full of meaning. Somewhere, a filmmaker just needs to find that world and fall in love.

Let’s hope they meet again—on the page, and on the screen.

Read More: