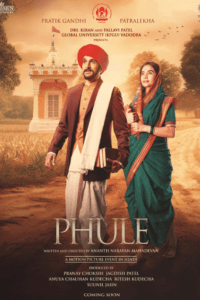

In a year where Indian cinema is being celebrated globally, the news of Ananth Mahadevan’s upcoming film Phule being asked to censor key scenes has reignited debate over the limits of creative freedom—especially when it comes to portraying caste-based narratives.

According to multiple reports this week, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has asked Mahadevan to remove direct references to caste groups such as Mang and Mahar in his Hindi-language biopic Phule, based on the lives of 19th-century reformers Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule. The board also reportedly demanded the removal of references to Manusmriti and the Peshwa regime—historical elements central to Phule’s anti-caste philosophy and activism.

Phule: The Censored Truth?

For many, this news is unsettling but not surprising. Phule, which aims to bring the reformers’ stories to a wider audience, is not the first film to depict these events. In fact, previous Marathi-language films—Satyashodhak (2023) by Nilesh Jalamkar and Mahatma Phule (1954) by P.K. Atre—have openly referenced caste oppression and key incidents from Phule’s life.

For many, this news is unsettling but not surprising. Phule, which aims to bring the reformers’ stories to a wider audience, is not the first film to depict these events. In fact, previous Marathi-language films—Satyashodhak (2023) by Nilesh Jalamkar and Mahatma Phule (1954) by P.K. Atre—have openly referenced caste oppression and key incidents from Phule’s life.

So why the pushback now?

According to one academic quoted in media reports, the difference may lie in the language and scale of the film. “The attitude is, let Phule be only for the Maharashtrians,” they noted. “He is not needed on a grand scale.” Mahadevan’s film, made in Hindi, was likely envisioned for a national audience. That, it seems, made all the difference.

In the upcoming film PHULE, a biopic of Jyotibai Phule, the Censor Board in India removed depictions of the very discrimination she fought. #CBFCWatch pic.twitter.com/bCCLMebQw5

— Aroon Deep (@AroonDeep) April 9, 2025

Mahadevan Responds: “Exaggerated and Unnecessary”

Amidst the swirling controversy, director Ananth Mahadevan has spoken out to clarify the situation. As reported by multiple media outlets, Mahadevan stated that while some “amendments” were suggested by the CBFC, there were no actual cuts.

“They had suggested some amendments, I wouldn’t call it cuts. I want to clarify that there are no cuts as such. We did so. They felt that the film should be watched by youth and everyone and it’s very educative,” Mahadevan said. “I don’t know why this whole storm of conflict and counter arguments are happening, I think it’s a little exaggerated and unnecessary.”

He added that a portion of the protest came from a misunderstanding, triggered by the trailer.

“The Brahmins got carried away by a two-minute trailer,” Mahadevan explained. “But there is nothing objectionable in the movie.”

The director also clarified that the decision to delay the film’s release was not due to CBFC pressure, but to calm social tensions and ensure a peaceful reception.

“The protest started between two groups, we wanted to calm them down, and tell them that, ‘It has nothing what you people are imagining’… So, the producer and the distributor got together and thought, ‘Let’s postpone it for two more weeks and clear all the controversies, talk to the media and let it reach them’,” he added.

A Pattern Emerging

The Phule controversy is part of a growing pattern—films that touch upon caste, systemic oppression, or social injustice often face censorship hurdles. What makes this instance particularly troubling is the irony: a film that honors a figure who fought censorship and discrimination is being scrutinized and debated before release.

Only recently, another film, Santosh (2024), directed by British-Indian filmmaker Sandhya Suri, faced a similar fate. Despite international praise, including screenings at the Cannes Film Festival and an Oscar nomination, Santosh was denied release in India by the CBFC. The film, which follows a female police officer investigating the murder of a Dalit girl, was reportedly deemed too politically sensitive due to its depiction of caste discrimination, police brutality, and misogyny.

Suri criticized the decision, calling it a “refusal to engage with reality.” Many echoed her sentiments, arguing that stories that dare to reflect uncomfortable truths are increasingly being silenced at home, even as they are celebrated abroad.

Why It Matters

When the CBFC mandates cuts to references like “Manu” or “Mahar,” it isn’t just editing—it’s erasure. These aren’t incidental details. They are part of well-documented history, critical to understanding the life and work of Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule. Sanitizing their stories risks turning powerful political legacies into hollow historical dramas.

It also highlights an uncomfortable double standard: caste realities can be acknowledged in regional cinema or international circuits, but not when presented to a wider Hindi-speaking audience.

A Larger Debate

These controversies raise deeper questions about the role of the CBFC. Should a certification board be acting as a moral gatekeeper? Or should it merely guide audiences while allowing creators to speak their truth?

In its current form, the CBFC continues to reflect larger anxieties about social instability and dissent. Films like Phule and Santosh are reminders that while Indian cinema is thriving globally, it still struggles to breathe freely within its own borders.

Jyotirao Phule strongly believed that lack of education was a major tool of oppression. His writings in Gulamgiri emphasized how ignorance was deliberately maintained to sustain caste hierarchies. That belief feels eerily relevant today—not just socially, but culturally.

As we celebrate Indian filmmakers on the global stage, it’s worth asking: what good is international recognition if we cannot confront our own truths at home?

Read More: